Life expectancy only seems to go upwards, but how far can it go? Meet some of the bioengineers wielding CRISPR technology to stop ageing in its tracks.

What if, further than reading and comprehending the code life is written in, genome sequencing could also rewrite DNA as desired? CRISPR, a technique enabling this with better productivity and accuracy than any before, has gotten many excited about this possibility.

Editing out problems

“In terms of speed, CRISPR is probably 10 times as quick as the old technology and five to 10 times as cheap,” said Professor Robert Brink, Chief Scientist at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research’s MEGA Genome Engineering Facility.

The facility uses the CRISPR/Cas9 process to make genetically-engineered mice for academic and research institute clients. Like many labs, Brink’s facility has embraced CRISPR/Cas9, which has made editing plant and animal DNA so accessible even amateurs are dabbling.

First described in a June 2012 paper in Science, CRISPR/Cas9 is an adaptation of bacteria’s defences against viruses.

Using a guide RNA matching a target’s DNA, the Cas9 in the title is an endonuclease that makes a precise cut at the site matching the RNA guide. Used against a virus, the cut degrades and kills it. The triumphant bacteria cell then keeps a piece of viral DNA for later use and identification (described sometimes as like an immunisation card). This is assimilated at a locus in a chromosome known as CRISPR (short for clustered regularly spaced short palindromic repeats).

In DNA more complicated than a virus’s, the cut DNA is able to repair itself, and incorporates specific bits of the new material into its sequence before joining the cut back up.

Though ‘off-target’ gene edits are an issue being addressed, the technique has grabbed lots of attention. Some claim it could earn a Nobel Prize. There is hope it can be used to eventually address gene disorders, such as Beta thalassemias and Huntington’s disease.

“Probably the obvious ones are gene therapy for humans, and agricultural applications in plants and animals,” Dr George Church of Harvard Medical School told create when asked of immediately promising areas.

Among numerous appointments, Church is a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and founding core faculty member at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

Last year, a team led by Dr Church used CRISPR to remove one of the major barriers to pig-human organ transplants – retroviral DNA – in pig embryos.

“We’re now at the point where it used to be that you would have to have a perfect match between donor and recipient of human cells, but that was because you couldn’t engineer either one of them genetically,” he said.

“You can engineer the donor so that it doesn’t cause an immune reaction. Now, you can have what are called, ‘universal donors’. That’s being used, for example, in making T cells that fight cancer – what some of us call CAR-T cells. You can use CRISPR to engineer them so that they’re not only effective against your cancer, but they don’t cause immune complications.”

Uncertainty exists in a number of areas regarding CRISPR (including patent disputes, as well as ethical concerns). However, there is no doubt it has promise.

“I think it will eventually have a great impact on medicine,” Brink said.

“It’s come so far, so quickly already that it’s almost hard to predict… Being able to do things and also being able to ensure everyone it’s safe is another thing, but that will happen.”

And as far as acceptance by the general public? Everything that works to overcome nature seems, well, unnatural, at least at first. Then it’s easier to accept once the benefits are apparent.

Professor Church – who believes we could reverse ageing in five or six years – is hopeful about the future. He also feels the world needs people leery about progress, and who might even throw up a “playing God” argument or two.

“It’s good to have people who are anti-technology because they give us an alternative way of thinking about things,” he said.

“[Genetic modification] is now broadly accepted in the sense that in many countries people eat genetically-modified foods and almost all countries, they use genetically-modified bacteria to make drugs like Insulin. I think there are very few people who would refuse to take Insulin just because it’s made in bacteria.”

Tale as old as time

A lot has had to happen to get us to this point. Since successful genome sequencing was first announced in 2000 by geneticists Craig Venter and Francis Collins, the cost of mapping DNA’s roughly three billion base pairs has fallen exponentially. Venter’s effort to sequence his genome cost a reported US$100 million and took nine months. In March, Veritas Genetics announced pre-orders for whole genome sequencing, plus interpretation and counselling, for US$999.

Another genetics-based start-up, Human Longevity Inc (HLI), believes abundant, relatively affordable sequencing and collection of other biological data will revolutionise healthcare delivery. Founded by Venter, stem cell specialist Robert Hariri and entrepreneur Peter Diamandis, it claims to have sequenced more human genomes than the rest of the world combined, with 20,000 last year. It has a goal of reaching 100,000 this year and over a million by 2020.

HLI offers to “fully digitise” a patient’s body – including genotypic and phenotypic data collection, and MRI, brain vascular system scans – under its US$25,000 Health Nucleus service. Large-scale machine learning is applied to genomes and phenotypic data, following the efforts at what Venter has called “digitising biology”.

The claim is that artificial intelligence (AI) can predict maladies before they emerge, with “many” successes in saving lives seen in the first year alone. The company’s business includes an FDA-approved stem cell therapy line and individualised medicines.

The slogan “make 100 the new 60” is sometimes mentioned in interviews with founders. Their optimism is not isolated. Venture capitalist Peter Thiel admits he takes human growth hormone to maintain muscle mass, confident the heightened risk of cancer will be dealt with completely by a future cancer cure, and plans to live to 120.

Bill Maris, CEO of GV (formerly Google Ventures), provocatively said last year that he thinks it’s possible to live to 500. And anti-ageing crusader, biological gerontologist Dr Aubrey de Grey, co-founder and chief science officer of Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS, whose backers include Thiel), has claimed that people alive today might live to 1000.

Longevity expectations are constantly being updated. Consider that in 1928, American demographer Louis Dublin put the upper limit of the average human lifespan at 64.8.

How long a life might possibly last is a complex topic and there’s “some debate”, said Professor of Actuarial Studies at UNSW Michael Sherris.

He said there have been studies examining how long a life could be extended if certain types of mortality, such as cancer, were eliminated, points out Michael Sherris.

“However, humans will still die of something else,” he adds. “The reality is that the oldest person lived to 122.”

Will we see a 1000-year-old human? It isn’t known. What is clear, though, is that efforts to extend health and improve lives have gotten increasingly sophisticated.

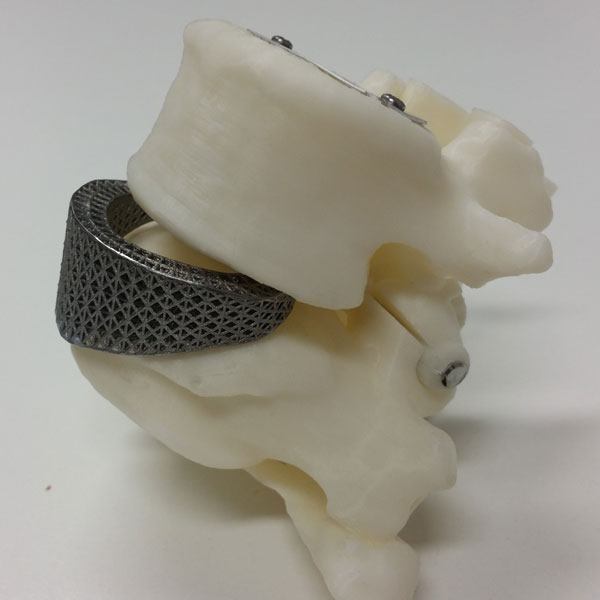

The definition of bioengineering has also grown and changed over the years. Now concerning fields including biomaterials, bioinformatics and computational biology, it has expanded with the ability to apply engineering principles at the cellular and molecular level.

A complete mindshift

Extended, healthier lives are all well and good. However, humans are constrained by the upper limits of what our cells are capable of, believes Dr Randal Koene. For that and other reasons, the Dutch neuroscientist and founder of Carbon Copies is advancing the goal of Substrate Independent Minds (SIM).

The most conservative form (relatively speaking) of SIM is Whole Brain Emulation, a reverse-engineering of our grey matter.

“In system identification, you pick something as your black box, a piece of the puzzle small enough to describe by using the information you can glean about signals going in and signals going out,” he explained, adding that the approach is that of mainstream neuroscience.

“The system identification approach is used in neuroscience explicitly both in brain-machine interfaces, and in the work on prostheses.”

No brain much more complicated than a roundworm’s has been emulated yet. Its 302 neurons are a fraction of the human brain’s roughly 100 billion. Koene believes that a drosophila fly, with a connectome of 100,000 or so neurons, could be emulated within the next decade. He is reluctant to predict when this might be achieved for people.

There’s reason for hope, though, with research at University of Southern California’s Centre for Neuroengineering pointing the way.

“The people from the [Theodore] Berger lab at USC, they’ve had some really good results using the system identification approach to make a neural prosthesis,” Koene said.

Koene counts being able to replace the function of part of a brain as the “smallest precursor” to whole brain emulation, with the end goal a mind that can operate without a body.