Algorithms and psych theories have converged to create emotionally intelligent facial recognition software for use in healthcare, HR, education and more.

A recent coalescence of psychological theories and computer vision is putting emotionally intelligent machines in our hands.

This is an observation by Andrew Moore, a former VP at Google and Dean of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU). Last year he predicted 2016 would be a “watershed year” for emotionally intelligent AI.

The work of psychologists influenced by Paul Ekman – who in the late-1970s distilled facial expressions into six basic emotions – and 3D reconstruction specialists (such as CMU’s Takeo Kanade) have converged in recent years. The result? Automated processes that do a pretty good job of detecting your emotional state.

“Some researchers at Carnegie Mellon who were doing this work made friends with some psychology professors at University of Pittsburgh, just down the road from Carnegie Mellon, and combined these two areas,” Moore said.

There are several recent products using this approach, combining Ekman’s Facial Action Coding System and algorithms to changes in deformable relative to non-deformable points on a face.

Releases include those by Kairos, Emotient (acquired in January by Apple for an undisclosed amount) and Affectiva. IntraFace, developed through a five-year CMU/University of Pittsburgh collaboration, was released in December as free research software.

MIT Media Lab spin-out Affectiva was first out of the blocks, commercially speaking, and formed in 2009. It has completed an analysis of over four million faces and over 50 billion data points in 75 countries, and its focus is in market research. The vast data accumulated is valuable in benchmarking across demographics for media and advertising customers, explained Gabi Zijderveld, VP Marketing & Product Strategy.

“We can really take advantage of deep learning approaches and create, very quickly, in a highly automated fashion, these algorithms that are very, very accurate,” she said.

The company’s co-founder, Professor Rosalind Picard, founded and leads the Affective Computing group at the Media Lab. She invented the term and discipline “affective computing” in 1994, outlining its principles in a 1997 book of that name. She defines it as “computing that relates to, arises from, or deliberately influences emotion or other affective phenomena.”

It isn’t just facial recognition either, and includes technology that can interpret our signs and is designed to be emotionally intelligent. An old example, the much-detested Microsoft Office Assistant Clippy, represents emotionally unintelligent AI.

At the time it was a badly overlooked topic, according to Picard. At its core, it is about showing more respect for human feelings. Consider the problem of vision, which “is affected by attention, and attention is what matters to you,” Picard wrote several years ago.

“Vision, real seeing, is guided by importance,” governing what is focused on.

A vision system that doesn’t consider attention could be missing the picture, so to speak.

“In the early days of Affectiva, we’d say look we have this cool new capability – we can read facial expressions,” she recalled.

“People are like ‘who cares about that, what’s that good for?’.”

Nowadays, emotionally intelligent machines are a sexier topic. Today Affectiva, which Picard left in 2013, claims over 1400 customers (with about a third of the Fortune 100), and in May had raised a total of $34 million in venture capital.

Pinning down an emotion

Affectiva’s software development kit 2.0 last year came with a range of seven emotions. IntraFace comes with five. The number is disputed with some experts putting it at 21 or more.

Besides the number of definable emotions actually in existence, the definition of emotion itself is contested. “It’s been said that there are as many theories of emotions as there are emotion theorists,” is one expert’s observation.

Definition itself isn’t a barrier to doing useful work, according to Picard, who explained in terms of her background in computer vision. This involved tough mathematical problems for content-based image retrieval, mapping perception and operating where precise descriptions didn’t exist.

“I told people let’s not argue about whether or not a particular rock is a piece of Everest, whether we can define this pebble or this rock at the base of Everest to be a part of Everest or this piece or that to be a part of emotion,” she said.

“Let’s just start climbing the mountain.”

What is it good for?

For Affectiva, early uses have been focused on engagement with digital content. This has included focus groups, pilots for TV shows, video games, and even human resources and legal depositions.

Companies and consumers will one day wonder how they ever lived without emotionally intelligent machines, and Affectiva believes an emotion chip and their technology will one day be found in all our smart devices.

Last year, the company made its software development kit available for Android, iOS, Windows, Linux and Mac OS X. End purposes will depend on user’s creativity.

MediaRebel recently launched a video deposition platform using Affectiva, tracking the expressions made by witnesses during testimony.

“There’s an automated transcript that’s in sync with the video, and then they overlay our technology to get emotion metrics and get analytics on the emotions,” explains Zijderveld.

“When you dive a bit deeper and think of how much time and money is spent to actually do that, you can see the value that a solution like that offers quite rapidly.”

The company’s work initially included both wearable technology and its Affdex platform, though it stopped making its Q Sensor in 2013.

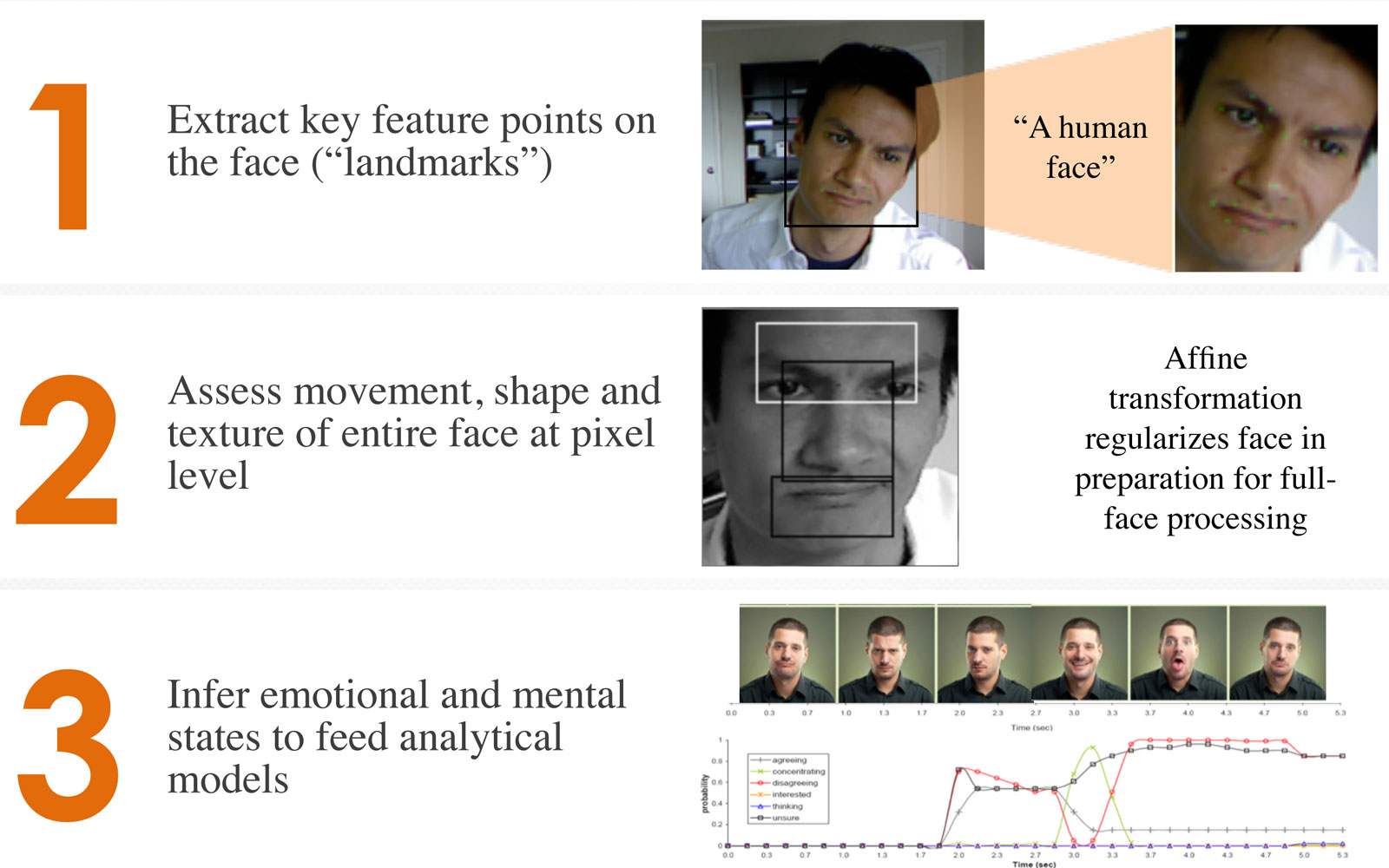

Affdex facial coding: How does it work?

Picard has continued the early affective computing focus on wearable sensors. Another business she co-founded, Empatica, began shipping its smartwatch, Embrace, this year. It monitors for stress and seizures, and measures electrodermal activity, temperature and motion.

Picard has continued the early affective computing focus on wearable sensors. Another business she co-founded, Empatica, began shipping its smartwatch, Embrace, this year. It monitors for stress and seizures, and measures electrodermal activity, temperature and motion.

Empatica’s E4 research sensor is being used for research in areas including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

What really matters

Early work in affective computing focused on autism, attempting to better convey emotional information to and from the sufferer.

Disorders involving emotion remain an area of great interest for researchers. Jeff Cohn of University of Pittsburgh, a professor of psychology and psychiatry and part of the team behind IntraFace, began affective computing research to understand the communication of depression within families.

According to the World Health Organisation, depression will be the leading source of disease burden by 2030. Improved diagnosis and treatment methods would be hugely impactful. Screening and diagnosis is still something that primarily uses self-reporting.

Cohn said new approaches he has been involved in “make possible automated audiovisual measurements of behaviours that clinicians and clinical researchers struggle to quantify”.

These tools have the potential to improve screening and diagnosis, as well as “identify new behavioural indicators of depression, measure response to clinical intervention, and test clinical theories about underlying mechanisms”.

He doesn’t see a future where interviews and questionnaires are replaced however. Critical aspects of depression – such as suicidal thoughts – are only assessable by language.

Reducing classroom boredom

Another area of great potential is around education. Moore believes it’d be enormously beneficial for educators to better know what was working in holding a class’s attention and delight – and what was failing.

“Can you imagine what the world would be like if education around the world was 20 per cent more effective because people were 20 per cent less bored?” he asked.

Affective’s software was used in MIT research, showing “great promise”. Published this year, it involved using emotional responses from preschoolers to customise how Spanish was taught, through a robot peer.

“What if these learning management systems would understand that a student is bored or confused or frustrated, and then adapt in real time to the emotions of the student?” Zijderveld said.

There have been comments made around the perceived ‘creepiness’ of emotionally intelligent systems being able to interpret our feelings and respond to them.

Ekman has voiced privacy concerns and Affectiva is aware of the sensitivity issues and has a strong focus on opting in and giving consent, recognising that emotions are “quite personal”.

Like any technology, the usual comments about “a double-edged sword” and the “in wrong hands …” apply here. Consider a repressive regime armed with affective computing, monitoring its citizens,, and being able to detect which ones were feigning loyalty.

There’s no evidence this could happen yet, but “it is our responsibility as engineers to be thinking about the future, so this is one of the things that concerns me,” Moore said.